Ineffective Theory

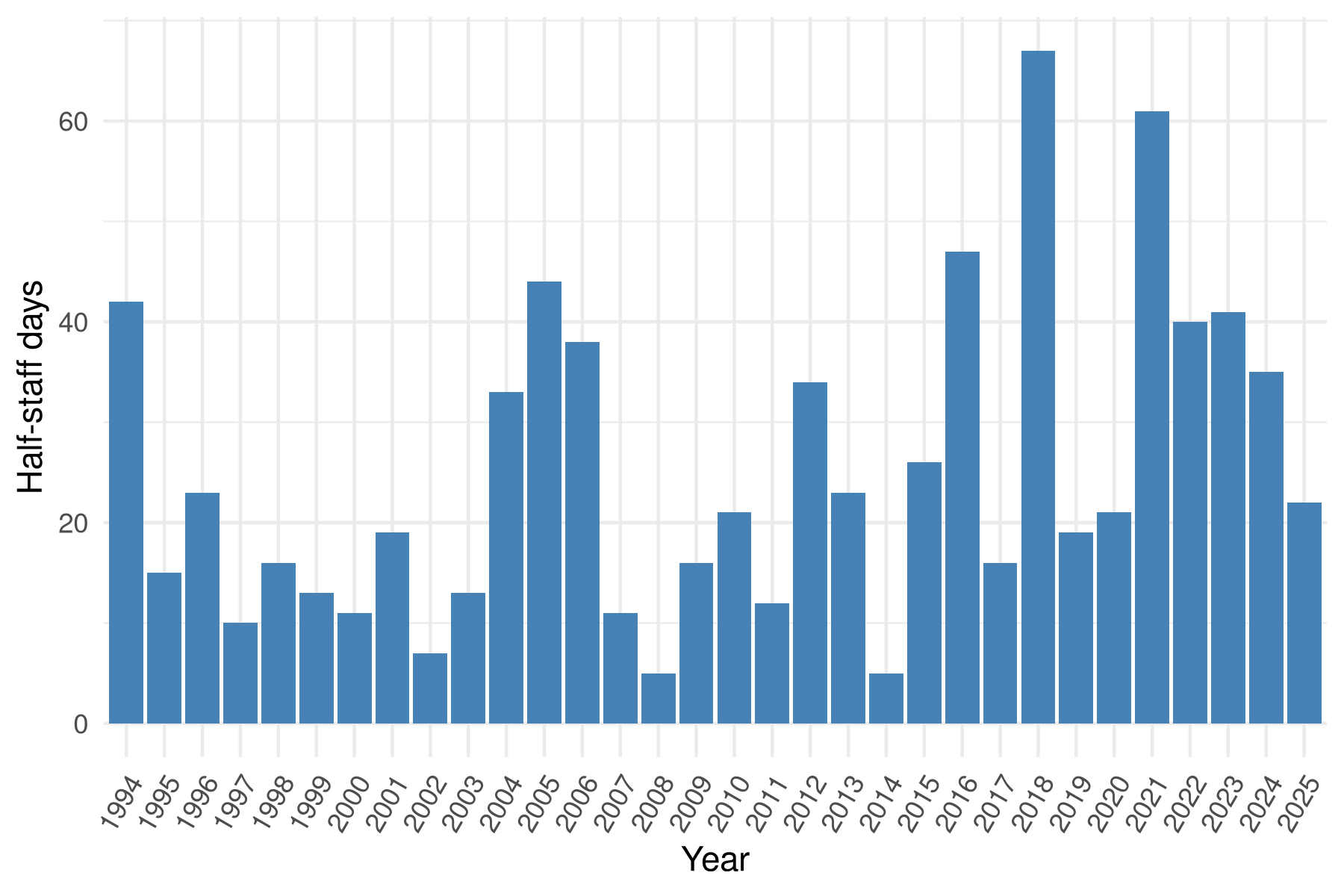

For a few years now, I’ve had this vague sense that the U.S. flag is at

half-staff more often than it used to be. This appears to be true.

This is generated from presidential proclamations downloaded from the federal

register. You can find the CSV I produced by processing this data

here. Many of these data points could easily be off by a few

days, since much of the processing was automated (by a combination of keyword

heuristics to find the relevant proclamations, and then AI to extract dates).

Even the stuff that I did by hand can easily be off by a day or two:

determining when a particular person was interred, and therefore when the flags

were restored to full height, is not always easy! Don’t rely on small

differences in the number of days: 20 vs 24 days may not be meaningful.

That being said, there’s a pretty clear overall trend, and two multi-year

periods during which the flag was lowered more than 10% of the time: 2004-2006

and 2021-2024. I was born in 1993 and my political memory begins around 2007

(when I began high school). My memory seems to reflect something real: the flag

is lowered two or three times more often now, than it was when I was in high

school.

I don’t know how seriously to take these trends. On the one hand, a lot of

these lowering are due to the deaths of major public figures. In that sense

we’re looking at a particular generation that overperformed in public service,

and has over the last few years begun to rapidly die off.

On the other hand, it’s hard not to feel that there’s been rising public

negativity since 2016. (This has been a favorite topic for Tyler Cowen, for example.) Start-dates vary, but not by that much. Depending the

color of your political skin, you associate this negativity either to “woke” or

to “Trump”. It is interesting to note that this rising negativity is also

reflected in the flag being lowered more often.

Price discrimination accomplishes: redistribution from rich to poor, without

government intervention, on a strictly voluntary basis, tending to increase

efficiency. What’s not to love?

We already accept price discrimination! Coupons famously serve this purpose

(among others), allowing price-sensitive customers to get access to cheaper

groceries while still charging the higher price to those who really don’t care.

Returns are also a form of price discrimination (if you think about risk as

part of the price). And neither of these mechanisms are perfect. Both favor the

highly conscientious as much as the price-sensitive, and coupons penalize the

desperate and the rushed.

I’m happy to go further. Stores want to discriminate based on price

sensitivity, but have trouble doing so, because the really central indicators

(income, savings) are not directly visible. So stores have to discriminate

based on crude proxies (are you using the app? what part of town are you in?).

It’s better than nothing, but we can imagine a better world. Give merchants

access to IRS income verification, and let them discriminate based on what they

actually care about. Universities do a pretty good job of price discrimination,

and this is part of how.

My feelings about price discrimination are not unconditional love. There’s one

form of price discrimination which is clearly bad no matter what moral hat I

wear. If you charge a higher price based on which customers are unable to shop

for alternatives, this is taking advantage of a non-competetive market in a way

which doesn’t tend to make the market any more competetive. It’s analogous to

the so-called “price gouging” that happens in an emergency, except without the

feature of drawing more resources to the task of acquiring necessary goods.

This is a pure tax on misfortune.

There’s also the sort of price discrimination made illegal under

Robinson-Patman. Recklessly

glossing: price discrimination can be unlawful when it has a good chance of

suppressing competition. As in the above example, these forms of price

discrimination are not increasing efficiency. Fortunately, the example above

would incur a great deal of opprobrium in any social climate I can imagine, and

price discrimination aiming to suppress competition (as opposed to simply

exploiting its absence) is already illegal.

And now for some possible objections. (This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive

list; for example, I’m deliberately not replying to “this benefits the

corporation at the expense of the consumer”. If you have nothing nice to

say…)

Redistribution is bad! This is not obvious. Government redistribution is

(presumptively, not always) bad, but this isn’t that. This is a private actor

finding that it’s within its own economic interest to perform redistribution.

This sort of “third-party redistribution” (distinct from charitable giving!)

already happens:

- When people choose to shop at local, or family-run, businesses. (Since the prices are likely a bit higher, there’s also some charitable giving here, but the ordinary surplus that a large chain would have gathered is being redistributed.)

- When stores offer veteran discounts. (In a competetive market, this one is redistribution from the average customer to the veterans, rather than charitable.)

- Insurance. (Insurance is, by definition, redistribution from the lucky to the unlucky.)

Now, it’s plausible that redistribution schemes from rich to poor generally hurt efficiency as a result of the new allocation of resources. But in the case of price discrimination, the act that results in redistribution is itself more efficient. So: assuming we aren’t caring about the welfare benefits of redistribution, it’s still not clear that this form of redistribution is net inefficient.

But it’s unfair! Yes, in a shallow sense. The fact that different people

have different amounts of money is also unfair, in an equally shallow sense. If

nothing else, there’s a pleasing symmetry here.

What if stores discriminate on the basis of race?

Here, in lieu of expressing a strong normative position, I will simply note a

polydactyl’s handful of facts.

-

A rational, self-interested actor will generally charge the higher price to the wealthier group.

-

Price discrimination on the basis of race is generally illegal (under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, in a “place of public accomodation”).

-

Laws against racial price discrimination are well-obeyed.

-

Discrimination on the basis of race in higher education is generally illegal (under the same Civil Rights Act of 1964).

-

Laws against discrimination on the basis of race in higher education are not well-obeyed.

-

A rational, self-interested actor will generally favor the wealthier group in college admissions.

I invite you to combine these facts with your moral intuitions and reach

whatever conclusion you may. For my part I don’t see a simple moral story into

which they all fit, and I don’t believe that price discrimination is

substantially related to racial discrimination.

I used to think Schindler’s List a beautiful movie. It’s a story of a man who

is, fundamentally, an outlaw. He has little allegiance to the society around

him; he is immune to the moral zeitgeist of the time; obeying the law is a

matter of practicality, not conscience. He wishes to run a business, but his

talent isn’t business, but -schmoozing- networking. He’s nice, in a

superficial way, while also not really caring. To be clear, he’s not an outlaw

in the “principled rebel” way. He’s a sleaze.

Schindler sees [1] a genuine business opportunity. The Nazis have neglected a

valuable workforce. Schindler threads the necessary needles and puts that

population to work. They don’t really need to be paid, and Schindler builds a

rather profitable business. As he does, he comes to identify with the source of

his profit. He realizes the good he has done, and comes to value the good

itself more than what led him to it. But we should not forget: what led him to

it was a sort of societal sin. He is a criminal. His was a criminal act, not

performed for an ideology, but for personal profit.

Schindler saved thousands of lives. Schindler broke the law for personal

profit. These are not contradictory parts of a complex man: they are

descriptions of the same act. This isn’t a murderer who saves a little girl

from an oncoming train, it’s a story of one decision, which is at once a sin

and a mitzvah.

That is the essence of the story. It’s beautiful. But rewatching the movie much

later, I can’t help but think that I was so focused on the story of Schindler

that I missed the substance of the movie. A movie has a story, but also has

themes, characterization, and so on. A beautiful story can be told by an ugly

movie.

The movie begins, and we meet Oskar. Schindler is calculating, Schindler is

greedy. He covets money, he covets gold. He is cunning, certainly, he is also

well connected, particularly to other semi-criminal businessmen. He is immune

to the demands of his nation, he serves only himself and his bank account. One

suspects international connections; at least he is unappreciative of the

distinction between a man of one nation (Oskar, a German) and a man of another

(Itzhak, a Jew). He is exploitative—the whole movie is about his

exploitation! He is manipulative—the whole movie is enabled by his

manipulation! He lacks compassion. In short he conforms to a very particular

stereotype.

But it’s a movie! Schindler’s character develops. His pleas to his friends to

join him don’t appeal to their thirst for money (with which he can no longer

fully sympathize): “Come on, I know about the extra food and clothes you give

them…”. He views gold as unvaluable: “this is gold! Two more people; they

would have given me two for it”. He is self-sacrificing. He even teaches Amon

Göth to appreciate that central Christian virtue, forgiveness. “Amon the

Good… I pardon you”.

In short, he has adopted Christian values, become a true Christian. It’s a

movie, it had to be so. Adopting Christian values is the only path to

redemption for someone like him.

[1] Well, in real life, Stern tells him. Let’s not add “business acumen” to the

already short list of Schindler’s apparent virtues. But for the consequences

of his actions, I’m sure we would consider Schindler a man with no redeeming

qualities.